Among the insights of New Yorker’s analysis of Obama’s campaign” is this interesting discussion of “celebrity blowback”:

“In July… a McCain ad compared Obama to Paris Hilton. What seemed to outsiders like a trivial, even ridiculous attack had an enormous impact inside Obama’s headquarters.

The campaign kept Obama away from celebrities as much as possible. A Hollywood fund-raiser with Barbra Streisand became a source of deep anxiety and torturous discussions. In Denver, celebrities who in past Presidential campaigns would have had major speaking roles were shielded from public view. “We spent hours trying to celebrity-down the Democratic National Convention,” the aide said.”

Interesting, since so much scholarship has recently trumpeted the importance and special legitimacy of celebrities on the public policy process, global diplomcay, and transnational advocacy campaigns. Dan Drezner’s article in TNI last November was optimistic about the role of such players, if not falling for the idea that they do it for pure altruism. Andrew Cooper’s recent book Celebrity Diplomacy paints a similarly rosy view of these actors. The journal Global Governance recently ran a forum on celebrity diplomacy with contributions by Cooper, Heribert Dieter and Rajiv Kumar.

If celebrities indeed have both special power and increasingly legitimacy in the policy process, why wouldn’t Obama’s handlers assume this metaphor might help rather than hurt him? Their reaction might be the best indicator that the credibility of celebrities in policy is overrated.

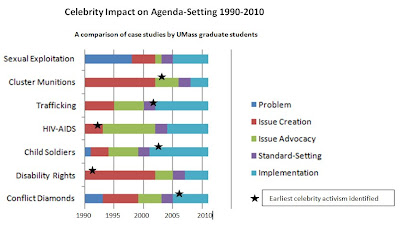

My graduate students have dug up some data suggesting an explanation. In my course on “Global Agenda-Setting” at University of Massachusetts, they have been tracing seven global campaigns that have taken place since the end of the Cold War, including the causal impact (if any) of celebrities. Thematic issues examined included HIV-AIDS, Disability Rights, Cluster Munitions, Child Soldiers, Trafficking, Conflict Diamonds, and Sexual Exploitation by UN Personnel. Overall, they found that while celebrities are all over many of these issues, in myriad ways, their influence on global agenda-setting tends to be minimal at best.

Here’s why: with the exception of issues where they are personally affected, celebrities generally don’t get involved in campaigns until they’re basically over. While one can’t infer too much from a few cases, and while the data here is limited by the exhaustiveness with which each student search for evidence of celebrity involvement, the seven cases they tracked suggest celebrities mostly endorse issues that already have a solid place on the policy agenda: it is rare for the glitterati to function as norm entrepreneurs or agenda-setters.

As the graph above demonstrates, celebrity involvement in the campaigns we studied typically post-dated the emergence of governance around a policy problem. For example, child soldiers began attracting celebrities not during the campaign of the late 1990s, but three years after the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child was signed; celebrities gravitated toward conflict diamonds in 2005, two years after the Kimberly Process had been negotiated. The graph above shows a similar pattern across four of our seven cases; in one case, Sexual Exploitation by UN Personnel, celebrities have stayed aloof entirely.

The campaigns we looked at where celebrity involvement may have significantly affected political opportunity structure of an issue are HIV-AIDS and Disability Rights, where celebrities functioned as living exemplars of the issues, helping to reduce stigma and popularize the notion that AIDS or disability can happen to anyone. While the self-interested nature of celebrity activism around these issues undermines the idea that they were purely altruistic, it also increases the cache of celebrity voices in the agenda-setting process because they are speaking as claimants as well as champions. Celebrities also tend to get involved much earlier in the policy process on these sorts of issues, giving themselves a chance to have a real impact rather than simply bandwagoning on others’ efforts.

Some other insights / thoughts:

To look more closely celebrity activism, it needs to be disaggregated into different varieties in order to tease out the causal importance of each on different phases in the global policy cycle. Our class identified at least six ways in which celebrities may assist in drawing attention to issues:

1) Lobbying, where celebrities use their access to elites to press for specific policy changes. Examples are Bono’s lobbying Jesse Helms on Debt Relief, or Edward Zwieck’s engagement with the diamond industry on conflict diamonds.

2) Campaigning, where celebrities visibly associate themselves with or endorse specific causes. Patrick Stewart played this role when he kicked off Amnesty International’s campaign on Violence Against Women; Ben Affleck has done this for the issue of child soldiering through his public association with Save the Children’s Rewrite the Future campaign.

3) Spokesmodeling, where celebrities lend their faces to public interest advertisements, whether or not for money. Gwyneth Paltrow’s advertising for the “I Am Africa” campaign constitutes an example.

4) Resource Transfers, where celebrities function as donors. This includes establishing foundations, such as Elton John’s AIDS Foundation; conducting benefits, such as LiveAid; and personal donations to causes.

5) Artifacts, when celebrities use their creative energy on projects to draw attention to specific problems. This can be overt, such as the film Blood Diamond and Kanye West’s song “Diamonds from Sierra Leone” ; alternatively, artists can embed issue advocacy into unrelated entertainment media, as Daughtry did with the music video for its ballad What About Now?.

6) Personification, when celebrities serve as poster children for particular issues because of their personal relationship to the problem. Michael J. Fox and Christopher Reeve did this for disability; Magic Johnson and Rock Hudson did it for HIV-AIDS; Emma Thompson personalized child soldiering when she adopted a former child soldier in 2003.

Second, different celebrities seem to be attracted to different types of activism, each of which has different costs, risks and effects. Leonardo diCaprio may be the celebrity most associated with conflict diamonds, but he has been relatively uninvolved in overt lobbying on the issue beyond interviews about the film itself.

Third, it’s possible to hypothesize that some of these strategies make a much bigger splash than others. Artifacts are useful for shaping public awareness, but generally come late in the policy chain and have minimal effect on agenda-setting and governance over global problems. Resource transfers no doubt provide much-needed capital for campaigns, but do they also serve as a means for celebrities to avoid greater involvement in issues or suggest to consumers that they can make a change simply by going shopping? Direct lobbying can matter in policy response, but imagine how celebrities could assist with the initial emergence of new issues by leveraging their unique access to elites much earlier in the agenda-setting process.

Charli Carpenter is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She is the author of 'Innocent Women and Children': Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians (Ashgate, 2006), Forgetting Children Born of War: Setting the Human Rights

Agenda in Bosnia and Beyond (Columbia, 2010), and ‘Lost’ Causes: Agenda-Setting in Global Issue Networks and the Shaping of Human Security (Cornell, 2014). Her main research interests include national security ethics, the protection of civilians, the laws of war, global agenda-setting, gender and political violence, humanitarian affairs, the role of information technology in human security, and the gap between intentions and outcomes among advocates of human security.

0 Comments