The grassroots advocacy campaign, Women on 20s, had a simple request: put a woman on the $20 bill by 2020 to commemorate the 100 year anniversary of the 19th amendment, which granted women the right to vote in the United States. Starting with a list of 15 women candidates, on-line voters cast an electronic ballot in the primary round and chose four finalists: Harriet Tubman, Eleanor Roosevelt, Rosa Parks and Wilma Mankiller. One month later, voters elected Harriet Tubman as their choice for the portrait on the twenty dollar bill. As the final votes were pouring in, Senator Jeanne Shaheen (D-NH) introduced S.925 Women on the Twenty Act, which is currently being considered by the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs.

The momentum of the campaign came to a halt when Treasury Secretary Jack Lew announced that a woman would appear on the redesigned $10 bill, but she would share the honor with Alexander Hamilton who is currently on the bill. Hillary Clinton commented

“I don’t like the idea that as a compromise you would basically have two people on the same bill. One would be a woman. That sounds pretty second class to me.”

Ben Bernanke is appalled by the decision

“Hamilton’s demotion is intended to make room to honor a deserving woman on the face of our currency. That’s a fine idea, but it shouldn’t come at Hamilton’s expense. As many have pointed out, a better solution is available: Replace Andrew Jackson, a man of many unattractive qualities and a poor president, on the twenty dollar bill. Given his views on central banking, Jackson would probably be fine with having his image dropped from a Federal Reserve note.”

Indeed, Andrew Jackson’s controversial past and disdain for the banking system were the primary reasons why Women on 20s initially sought to put a woman on the twenty dollar bill.

As with many advocacy campaigns, a confluence of factors most likely contributed to the announcement that a woman would be (co-)featured on the $10 bill. The decision to redesign the $10 was made in spring 2012 and the Treasury insists that security concerns (counterfeiting threats) trump political concerns when it comes to redesigning currency (the $10 bill was last updated in 2006 while the newest $20 appeared in 2003). In spring 2012, US Treasurer Rosie Rios seized the political opportunity created by this decision and planted the idea of featuring a woman on the currency. This sequence of events suggests that putting a woman on U.S. money was already on what Kingdon calls the governmental agenda (those items getting attention). By skillfully using social media as the organizational platform from which to launch a public debate, framing the problem as urgent and calling for action before the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment, the Women on 20s campaign was an important catalyst that moved the issue onto the decision agenda (those items being considered for action).

Clearly, putting a woman on either a $10 or $20 bill will not solve problems of gender inequality or shatter the glass ceiling; it will not increase the number of women in positions of power or reduce gender discrimination (see Kirsten West Savali’s and Esther Cepeda’s critiques). Yet, symbols, like paper money, matter; they constitute and construct our national narratives, our national identity and our political and social lives. This battle is one among many that women in the US are fighting to achieve recognition and equality. Indeed, symbolic politics are an important and effective tactic used by advocacy networks to ignite change, shift understandings of issues and create rallying points. So, what is the symbolic value of putting a woman on US currency?

Some argue that paper money is practically obsolete, so the symbolic shift is meaningless and a waste of time.

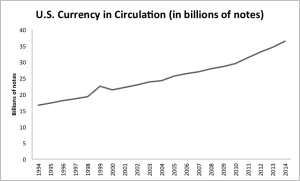

The graph below shows that overall, there is more cash in circulation today (36.4 billion notes) than in 1994 (16.6 billion notes) (for data).

A report released in April 2014 by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco (FRB-SF) finds that despite frequent predictions of the demise of cash, it is the most used retail payment instrument making up 40% of consumers’ monthly transaction activity. By value, cash accounts for only 14% of total consumer activity; this means that consumers make frequent low-value transactions in cash. Surprisingly, 40% of 18-24 year olds prefer cash as a mode of payment. 55 percent of consumers with household incomes less than $25,000 per year prefer cash over non-cash payment instruments. Thus, cash is not obsolete. Consumers still use cash albeit for lower-ticket items and importantly, certain demographics–the young and low socio-economic status groups–frequently interact with cash. This demographic data is important because advocacy campaigns are prone to what Schattschneider calls the mobilization of bias, which tends to privilege elite interests or as Savali argues “white feminists.” [Women on 20s voters’ demographic data does not include a breakdown by race or socio-economic status.] We need to conduct further research to determine whose interests the campaign represents, but in terms of who interacts with money, the FRB-SF reports indicates that it tends to be underrepresented groups.

Also, while the FRB-SF report does not include data on under-18s, I would venture that our most impressionable citizens—children—primarily use, receive and handle cash. The tooth fairy still puts hard currency under the pillow. Babysitters are still paid in cash. Common Core math worksheets still feature images of U.S. currency to teach financial literacy and counting in K-12 classes. Schools are important sites of socialization and cash still figures prominently in the symbolic stock they impart to our children.

Is the symbolic value of putting a woman on U.S. currency lost if a woman is co-featured on the $10 bill instead of exclusively featured on the $20 bill? Yes.

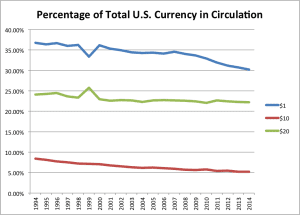

As of December 31, 2014, 5.2% of total bills in circulation were $10 bills (1.9 billion bills), while $20 bills comprised 22.3% of total bills in circulation (8.1 billion bills). The graph below shows that in terms of percentage of total U.S. currency in circulation, the $20 outpaces the $10 and this is consistent over time.

Moreover, the $10 bill’s circulation is in decline as compared to the $1 and $20 bills’ circulation as the graph above shows. Between 1994-2014 the share of $10 bills in the total pool of bills in circulation decreased by 38% compared to an 8% decrease for the $20. So, not only do we see fewer $10 bills today compared to $20 bills, but we also see fewer $10 bills than we did twenty years ago. The symbolic power of putting a woman on US currency is diminished if she is the only one to share a bill with another individual and if that bill’s circulation is in decline.

So, while others have argued that this campaign is about removing Andrew Jackson from the $20 bill, I would argue that the symbolic significance of the campaign is about making women visible in the economic and historical imaginary of our nation. Women have been featured on uncommon, minimally produced and briefly circulated currency in the past (Susan B. Anthony and Sacagawea on the $1 coin; Martha Washington on the 1886, 1891 and 1896 silver certificates) that remain hidden in vaults and coffers. The U.S. already lags behind several countries that recognize women on bank notes including Syria, Turkey and Argentina; the U.K. recently placed Jane Austen’s portrait on the £10 note (but of course British pounds already feature Queen Elizabeth II and other women). It is time to put a woman on a highly circulated, visible currency like the $20.

Maryam Z. Deloffre is an Associate Professor of International Affairs, Director of Dean’s Scholars and Director of the Humanitarian Action Initiative at the Elliott School of International Affairs; a Mercator Fellow at the DFG Research Training Group – Standards of Global Governance (Germany); and an Associate Senior Fellow at Centre for Global Cooperation Research, Universität Duisburg-Essen (Germany). Her research focuses on the dynamics of global and humanitarian governance, humanitarian standard-setting, humanitarian and non-governmental organization (NGO) accountability, NGOs, and locally-led humanitarian assistance.

0 Comments