This is a guest post from Tana Johnson, an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Political Science at Duke University. She is the author of Organizational Progeny: Why Governments Are Losing Control over the Proliferating Structures of Global Governance (now available in paperback, Oxford University Press). Van Nguyen is an undergraduate at Duke University, majoring in Public Policy and Political Science. She is completing a senior honors thesis on inter-governmental institutions and immigrant integration.

Within its first year in power, the Trump administration has transformed the U.S.’s position toward several international agreements: it has exited negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), signaled its intent to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, and promised to revamp the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Full-fledged international organizations, like the United Nations or NATO, are numerous and costly – so, will they be next? If budgets are reflections of values, then the Trump administration’s new budget proposal provides clues. Here’s what you need to know.

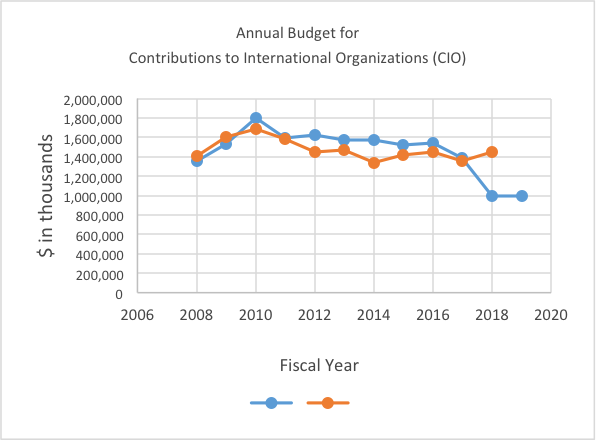

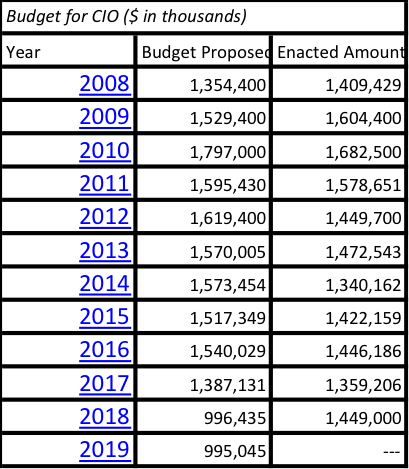

“Contributions to International Organizations” Faces a Big Reduction.

In the fiscal year (FY) 2019 budget, international organizations would be hit most directly through the discretionary item “Contributions to International Organizations” (CIO). This covers the dues, quotas, and other resources that the U.S. gives to inter-governmental and non-governmental international organizations. Under the two Obama administrations, CIO figures peaked in 2010 and then gradually declined. But the Trump administration’s proposed CIO of $995 million would be a steep decline: that’s a 31% decrease from final FY2018 congressional appropriations, and a 27% decrease from the FY2017 enacted amount.

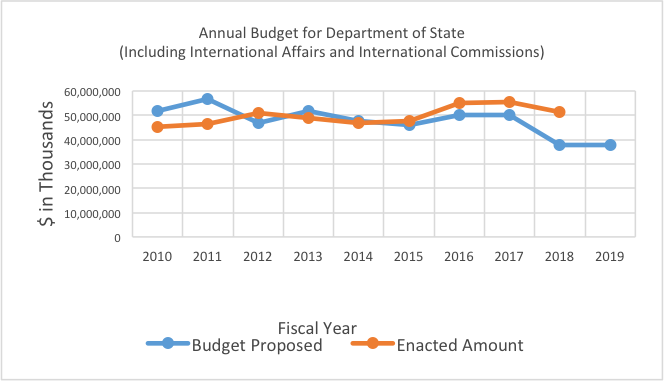

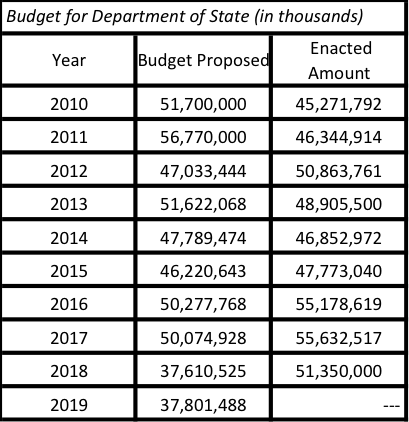

International Organizations Also Could Take a Hit through Reduced State/USAID Funding.

International organizations, along with other foreign policy activities, would also takean indirect hit through reduced funding for the State Department and the US Agency for International Development (USAID). After including international commissions, the FY2019 budget proposal recommends $37.8 billion for the State Department. That might sound like a lot, and it’s a $191 million increase over the FY2018 budget proposal. But it’s much lower than State’s actual average expenditures during the past decades, and it’s a 32% decrease from the FY2017 enacted amount.

This Is Part of a Larger, but Controversial, Tactic.

Direct and indirect hits to funding for international organizations are part of a broader rethinking of U.S. policy. The Trump administration justifies these budget recommendations as part of a new approach that tries to “influence other donors to give a greater share.” A related aim is to get U.S. agencies to think harder about the extent to which the international organizations they work with actually “advance American interests.”

By threatening a reduction in resources, the Trump administration is attempting to unsettle not only other countries, but also actors within the U.S. executive bureaucracy. However, Democratic and Republican leaders have bristled at this tactic. This was especially demonstrated by bipartisan support for the Senate Appropriations Committee’s resistance to similar budget cuts proposed last year.

Some International Organizations Would Be Hit Harder than Others.

Scores of international organizations receive U.S. funds. But to see some of the differential effects the proposed budget would have, let’s take a closer look at four big organizations: the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the World Bank/International Development Association (IDA), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the United Nations (UN).

NATO

NATO is funded through two methods. One is direct: common and joint funding efforts, which are like membership fees assessed through an agreed cost-share formula based on Gross National Income. The other method is indirect: countries’ spending on national defense. For the first, the FY2019 proposal budgets $70.1 million. But the second method skews things.

That’s because, although NATO members agreed in 2006 to spend a minimum of 2% of their country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to defense, some members have not reached that. Meanwhile, due to the huge United States defense budget (which is determined independently from NATO involvement), the US represents 72% of NATO’s entire defense spending. This creates a misconception that the United States covers 72% of NATO’s costs. Although that figure isn’t accurate, huge U.S. defense expenditures do result in NATO dependency on the U.S. With the Trump administration’s embrace of military build-up, that indirect (but important) contribution to NATO would not be in jeopardy, unless the U.S. made some dramatic move to withdraw from the organization.

The World Bank/IDA

Unlike many international organizations, the World Bank operates according to a weighted voting system that allocates power over decisions in rough proportion to the resources a country has contributed to the organization. That disincentivizes sharp cuts to contributions, because decision-making power could also be impacted. The World Bank is also somewhat protected because the money it channels to countries comes not just from member-country contributions, but also from resources like loan repayments or sales of bonds on financial markets.

A particular part of the World Bank – the International Development Association, which provides funds to the poorest countries at low or zero interest – is more exposed to the whims of member-countries, especially the wealthy donors. For IDA in FY2019, the Trump administration proposes contributing $1.097 billion. This is an unchanged amount from the Trump administration’s FY2018 proposal but a 21% decrease from the Obama administration’s FY2017 proposal. It also accompanies a broader change: for the past two years the United Kingdom, not the United States, has been the biggest IDA contributor.

The OECD

While NATO and the World Bank enjoy some built-in buffers against current U.S. tactics, other international organizations are more vulnerable. For example, member countries fund the OECD through voluntary and assessed contributions. Assessed contributions cover the general budget (Part 1) and the budget for specific programs that are of interest to subsets of the membership (Part 2). In FY2017 the U.S. was, by far, the biggest contributor to Part 1: it delivered 20.6% of the OECD’s general budget, while Japan took second place at only 9.4%. However, in the budget proposals for FY2018 and FY2019, the Trump administration did not specify any amount to contribute. Instead, figures for both proposals were footnoted with “support for OECD to be determined.” It’s easy to read this as the U.S. sending a shot across the bow.

The UN

The UN is primarily funded by payments made by its 193 member-countries. Payments are assessed for each country according to a formula that factors in Gross National Income and population. Historically, the U.S. has been the biggest contributor to the UN – and even though its share has declined as the UN’s membership has grown, today the U.S. alone funds about 22% of the UN’s regular budget and 28% of the UN’s peacekeeping operations. In the FY2019 proposal, the Trump administration budgets $442 million for the UN. This is essentially the same as the amount that the in-coming Trump administration proposed for FY2018, but it’s a 25.3% decrease from the amount that the out-going Obama administration proposed for FY2017.

The Budget Proposal Sends Strong Signals, Even If It Doesn’t Pass.

The FY2019 budget proposal is worrying for people across ideological lines. Traditionally, both Democrats and Republicans perceive at least three ways in which international organizations advance U.S. interests: keeping citizens safe, supporting moral imperatives, and building economic prosperity. But according to various policy experts, including those associated with the Better World Campaign and the International Refugee Committee, cutting funding for international organizations would destabilize the U.S.’s security and its global agenda. Last year, even the conservative Heritage Foundation cautioned against drastic, immediate cuts that could disrupt existing international initiatives.

Such pushback is why many of the cuts that the Trump administration proposed last year didn’t pass in Congress. And that certainly could happen again with the proposed FY2019 cuts. Nevertheless, the current budget proposal sends strong signals.

International organizations, and the parts of the U.S. government that interact with them the most, will need to be on notice. For now, some organizations are buffered from sea changes in the U.S. government. For instance, NATO is relatively safe because U.S. defense spending will continue to be high, and the World Bank is relatively safe because contributions are linked with vote shares.

But others, such as the OECD and the UN, are more vulnerable. And even NATO and the World Bank would not be safe indefinitely. The FY2019 budget proposal suggests serious skepticism about whether international organizations, which are largely funded by American money, continue to serve American interests. This is a question that goes beyond one president, or one administration – and it is a dilemma that international organizations must heed, counteract, or answer in the coming years.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

0 Comments