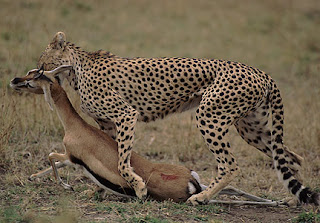

The big cats in political scientists like to hunt big game, the book contract at a “major university press.” Landing such a catch can feed oneself and his or her cubs for a long time, even for a lifetime. The “book at a major university press” can get you tenure. You will never have to eat again.

Book editors are wily prey, however, and have adapted to their dangerous environment through a number of clever strategies, the most important of which is not answering their email. Another behavioral modification to survive in this Darwinian world of eat-or-be-eaten is the platitude. “This book is not for us, but I am sure it will find a good home. Please consider us an outlet for your future work.”

Increasingly rare in the wild, political scientists have an organized game park — the conference book room. There they can stalk their prey in an environment somewhat approximating a natural environment, with e ditors surrounded by their press’ books in a book stall. They are sitting ducks. To escape, these wily creatures have been known to use their weakest as shield. Editorial assistants look just like book editors and can distract hungry academics just long enough for book editors to escape. Lured by the business trip to San Diego, these poor, young, ambitious employees are sacrificed in the interests of their bosses.

ditors surrounded by their press’ books in a book stall. They are sitting ducks. To escape, these wily creatures have been known to use their weakest as shield. Editorial assistants look just like book editors and can distract hungry academics just long enough for book editors to escape. Lured by the business trip to San Diego, these poor, young, ambitious employees are sacrificed in the interests of their bosses.

Poor, poor Chuck Myers. Against David Lake he did not stand a chance.

Press representatives have no choice though but to participate in these academic safaris as the hunters hold exclusive control over their main food source – the book that actually sells. Book editors are foragers in a scarce, overpopulated world, the camels of the academic desert. Over time, they have developed strong stomachs capable of digesting book prospectuses that at one time would have been impossible to consume. They have even been known to publish books about zombies in times of true desperation and starvation. To protect themselves from noxious odors, the most advanced editors have no sense of smell. Others simply hold their nose. It is a dog-eat-dog world.

Not all hunters stalk in the same way. Some charge headstrong into the fight, brandishing their prospectus in one hand while shielding, to the degree they can, their greatest vulnerability – their sense of self-esteem. More experienced political scientists generally prefer a more delicate dance that requires more effort but has a greater chance of success. They browse books, ask about the family, lulling the editor into a false sense of security. Then they pounce. “I have a book you might be interested in.”

Editors are not completely defenseless, however. If they cannot hide, they can counterattack through the right of exclusive review. This turns the tables, holding off the author’s strike for months, sometimes even years. The hunter has become the hunted. Press reps also engage in diversionary tactics. “I think that Cambridge might be interested in this book.” There is no loyalty among book editors. It is every press for itself. John Haslam might suffer a brutal attack, but Roger Haydon lives another day. It is just business. That’s all.

There is fierce competition among academics for access to this increasingly scarce commodity ,of course. If one browses the book stall too long, an interloper can step in. The political scientist must bide his time and circle back around later. By this time the carcass might be picked clean and other sources must be sought out. Academics live on borrowed time. The tenure clock is ticking. The stomach is growling. With the stags all gone, they must lower their sights – the rabbit, otherwise known as the commercial press. While not as nourishing, it can give the political scientist the strength to fight another day.

Rathbun is a professor of International Relations at USC. Brian Rathbun received his Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of California, Berkeley in 2002 and has taught at USC since 2008. He has written four solo-authored books, on humanitarian intervention, multilateral institution building, diplomacy and rationality. His articles have appeared or are forthcoming in International Organization, International Security, World Politics, International Studies Quartlery, the Journal of Politics, Security Studies, the European Journal of International Relations, International Theory, and the Journal of Conflict Resolution among others. He is the recipient of the 2009 USC Parents Association Teaching and Mentoring Award. In 2019 he will be recognized as a Distinguished Scholar by the Diplomatic Studies Section of the International Studies Association.

Brilliant, Brian!

“They have even been known to publish books about zombies in times of true desperation and starvation.”

Oh, snap!

Amusing and depressing at the same time…