In 1963, JFK predicted that there would be as many 25 nuclear powers by the 1970s. Yet here we are, some 70 years later, and the number of states believed to possess nuclear weapons has grown from 4 to 9. Why haven’t more states joined the club?

A variety of factors are undoubtedly at work (see this piece by Gartzke and Joon for a good attempt at bring systematic evidence to bear on this question). In this post, I am going to discuss one in particular: what William Spaniel refers to as “butter-for-bombs” agreements, wherein one state makes concessions to another in attempt to dissuade them from proliferating.

I focus on “butter-for-bombs” agreements here not because I believe them to be the single most important explanation for why so few states have gone nuclear, but because their occurrence has escaped the notice of many observers of international politics, and because their viability is not intuitively obvious. That some states might be willing to buy off potential proliferators is not surprising, of course. But the fact that potential proliferators can, under certain circumstances, credibly commit to honor such an agreement is. At least, to anyone who’s been paying too much attention to North Korea’s theatrics and not enough to instances of more successful “butter-for-bombs” agreements (such as those involving Libya, South Korea, and Australia.)

What keeps a potential proliferator (henceforth state B) from taking the concessions offered by the other state (henceforth A) and then turning around and developing nuclear weapons anyway? Well, according to the formal model that William analyzes, it’s the promise of receiving a better outcome in every period coupled with the desire to avoid the costs of actually building the weapons. Yes, B expects to be compensated each and every period in this model, but each and every time B chooses not to go nuclear, that compensates A.

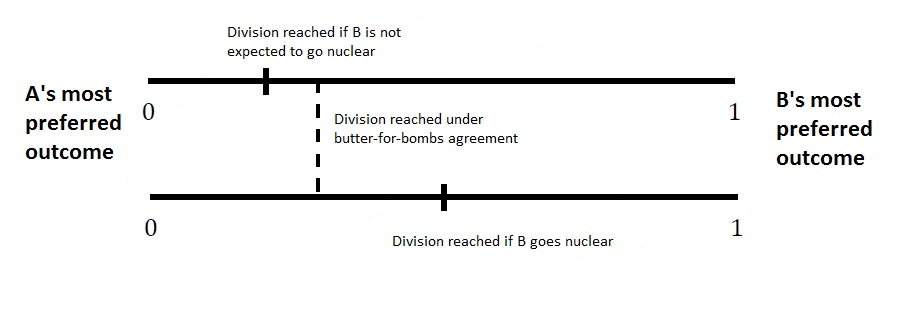

The following figure, which I’ve adapted from the one in William’s paper, might help clarify things.

Suppose A and B have substantive disagreements unrelated to B’s nuclear program. The top line represents possible divisions of the disputed benefits when B is not expected to go nuclear, and the bottom line represents possible divisions when B does go nuclear. The solid vertical lines running through these reflect the divisions that we would expect to be reached as the result of bargaining. The dashed line connecting the two horizontal lines reflects the terms of a butter-for-bombs agreement. The important insight here is that these agreements are stable because they give both sides just enough of what they want. Threatening to go nuclear, only to then be bought off by A, leaves B better off than they would be if A had no expectation of B acquiring nuclear weapons. That is, the mere potential to shift the distribution of power brings B benefits here. To be sure, A doesn’t love having the threat of B going nuclear hanging over their head in perpetuity, since this requires them to compensate B in each and every period. But the fact that B would have to incur some cost if they’re to ever make good on their threat allows A to insist upon terms that are better for A than those the two sides would reach if B ever actually did so. So long as the price of buying B off is not too large, that just might be worth it for A.

Of course, sometimes it won’t be. As William discusses in the paper, “butter-for-bombs” agreements are not always viable. If acquiring nuclear weapons would allow B to insist upon terms that are much more favorable to B, then A would have a credible threat to attack B preemptively instead of buying B off…and this threat will typically prevent B from developing nuclear weapons. (At least, in this model, where for the sake of simplicity, William assumes away the possibility of developing weapons in secret, or in underground facilities and so forth.) If acquiring nuclear weapons would only allow B to insist upon slightly better terms, then A doesn’t take B’s threat to go nuclear very seriously. But William discusses a few examples of cases of such agreements, and I for one am persuaded that we’ve been overlooking an important piece of the puzzle.

Not only does William draw our attention to a set of agreements we might otherwise have overlooked, but he offers some surprising insights about when they are most attractive. Specifically, your intuition probably tells you that if it was possible for states to wave a magic wand and lower the cost of acquiring nuclear weapons, they would do so. After all, if the mere threat of going nuclear can bring bargaining leverage, as actual possession thereof presumably does as well, what could a potential proliferator possibly gain from allowing this cost to remain as high as it typically is?

Simply put, when the cost of going nuclear is too low, B gains too much bargaining power, and A loses all interest in offering concessions. B has no interest in giving A a reason to attack. In order to benefit from possessing an ability to develop nuclear weapons without ever having to incur the costs of actually doing so, B must find those costs small enough to be bearable but large enough to be unattractive.

There’s much more detail in the paper. I strongly encourage you all to go read it. But hopefully this post helped you to appreciate why “butter-for-bombs” agreements have been successful in keeping some states from joining the nuclear club.

I am an assistant professor of political science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. I mostly write here about "rational choice" and IR theory. I also maintain my own blog, fparena.blogspot.com.

0 Comments