“This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.” So spoke Winston Churchill, after the Allied victory in the Second Battle of El Alamein. We could say much the same of his defeat in the 1945 general election.

A core assumption underlying most of the work analyzing the impact of domestic politics on international relations is that leaders want to remain in office. Insofar as ensuring national survival, territorial integrity, and policy autonomy might help leaders retain power, focusing on political ambition often does not tell us anything more than we might get from a state-centric approach. But there are some important exceptions. For one, democracies rarely if ever fight wars against one another. The fact that different institutions create different incentives for self-interested leaders may have something to do with that. For another, we often attribute the occurrence (or continuation) of wars to electoral motivations. I myself argued for a long time that Obama was pursuing the same strategy in Afghanistan that Nixon pursued in Vietnam – don’t lose the war until you’re a lame duck.

Most of these arguments, however, assume that a leader’s career ends once he or she leaves office. Yet this is not the case. Many leaders eventually make a comeback, returning to office after some time out of power. The British electorate deemed Churchill less suitable for managing the postwar economic recovery than international crises, and so favored the Labour Party in 1945. Yet they once more turned to the Churchill and the Conservatives in 1951 after the Labour Party had achieved most of what it set out to do. If we were to limit our attention to the 1945 election, we might conclude that Churchill did not benefit electorally from victory in WWII (as I myself once did), even though Churchill’s wartime record contributed to his return to power.

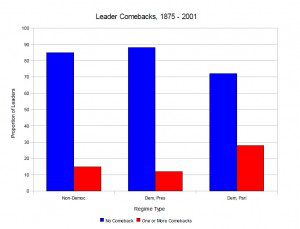

As Kerim Can Kavakli demonstrates, though, the frequency of leader comebacks varies significantly by regime type. Specifically, leaders of parliamentary democracies are more than twice as likely to return to power than leaders of either non-democratic states or leaders of presidential democracies.

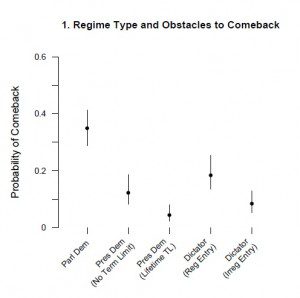

Though presidential democracies and non-democracies appear very similar in this respect, the reason that leaders of these regimes are unlikely to return to power is not the same. In presidential systems, leader comebacks are rare in large part because they are often constitutionally prohibited. In non-democratic systems, they are rare in part because such leaders are often punished when they leave office. Strangely enough, returning to power appears to be a bit more for those who have been executed. There is, however, variation within these broad categories, and the difference between parliamentary systems and other regimes remains even after we account for the most obvious obstacles to leader comebacks.

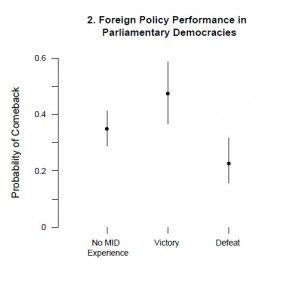

Kerim argues that the likelihood of returning to power depends both on regime type and the leader’s record. On the one hand, delivering peace and prosperity does nothing to help leaders return to power if they are constitutionally prohibited from doing so, as Bill Clinton is fond of lamenting. On the other, an absence of institutional barriers hardly matters for leaders whose record leaves them with few supporters, however much Ehud Olmert might want to believe otherwise. Kerim goes on to demonstrate that the outcomes of international conflicts are strongly associated with the likelihood that leaders return to power in parliamentary democracies, but not in presidential democracies or non-democracies.

There are broad implications to these findings. Empirical analyses that focus on leader reputations ought to consider not only the length of the current spell, but whether a leader has previously held power. Any argument that links accountability to differences in behavior with respect to international politics ought to apply more clearly to parliamentary democracies than presidential democracies. The incentive to gamble for resurrection, long associated with democracies, might only apply to presidential democracies, since leaders of parliamentary systems always have something to lose by losing wars.

I am an assistant professor of political science at the University at Buffalo, SUNY. I mostly write here about "rational choice" and IR theory. I also maintain my own blog, fparena.blogspot.com.

0 Comments