My frequent collaborator Jon Monten and I have a guest post on the new Chicago Council on Global Affairs blog Running Numbers. As our readers likely know, the Chicago Council runs periodic surveys about public attitudes towards foreign affairs and has historically run a number of important surveys of elite opinion. I’m cross-posting our piece here.

For many observers of American politics, the fight over the nomination of Chuck Hagel as the next Secretary of Defense is indicative of growing partisan acrimony in the conduct of US foreign policy. However, concerns about intensifying partisanship in foreign affairs are not new. A number of scholars including Shapiro and Bloch-Elkon, Trubowitz and Mellow, and Bafumi and Parent have warned that, in the two decades since the end of the Cold War, partisanship in foreign policy has been on the rise. According to this narrative, US foreign policy since the end of World War II was underpinned by broad, bipartisan support for an international strategy based on both projecting military power internationally and a commitment to multilateral institutions and agreements. Many of these same scholars including Kupchan and Trubowitz now warn that the bipartisan consensus in favor of this strategy – commonly referred to as “liberal internationalism” – is now unraveling. These scholars cite a number of explanations driving this trend, such as the end of the threat posed by the Soviet Union, ideological polarization among the parties, and generational change. From this point of view, the Bush administration’s embrace of unilateralism after September 11th was not an aberration, but rather reflected a long-running and irreversible trend.

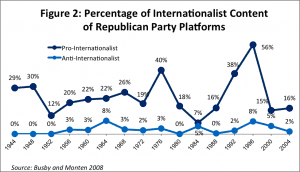

About five years ago, we asked ourselves what evidence we could bring to bear on assessing this claim. We looked at a variety of data: Congressional voting, party electoral platforms, Presidential State of the Union speeches, public opinion data (including survey data collected by The Chicago Council on Global Affairs), and information on the educational and biographical backgrounds of individuals serving in high-level foreign policy positions. If the claim that support for liberal internationalism was in decline were accurate, we would expect to see evidence of this decreasing support in each of these areas. Instead, as we demonstrated in a 2008 piece in Perspectives on Politics and a subsequent 2012 piece in Political Science Quarterly, we found a more mixed picture than what the conventional wisdom suggests. For example, when looking at Presidential State of the Union Addresses since 1950, we found that the pro-internationalist content of these speeches – defined as the number of statements favorable to building international institutions and new international commitments – declined from a Cold War peak but nonetheless remains robust (Figure 1).

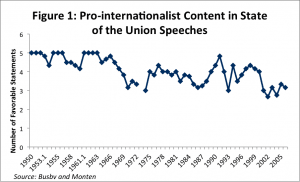

Similarly, the level of internationalist content in the electoral platform of the Republican party peaked in the mid-1990s, and has since declined to its approximate Cold War-era level (insert Figure 2).

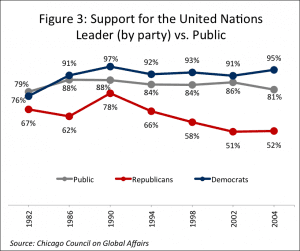

At the same time, U.S. political elites have clearly become more polarized in their attitudes towards the United Nations (Figure 3).

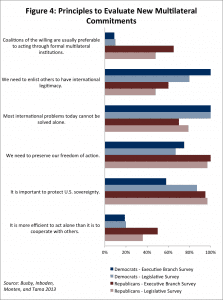

We recently supplemented this evidence with a new source of data – attitudes among foreign policy professionals with experience serving in Congress and Executive Branch agencies. The purpose of these surveys was to get at not only what U.S. foreign policy elites thought of different forms of international cooperation, but their underlying reasons for holding these views. Again, as we discussed in two pieces in Foreign Affairs in May 2012 and in January 2013, we found robust bipartisan support for a number of international organizations and agreements, including NATO, the World Bank, the WTO, and the IMF. However, the principles Democrats and Republicans used to evaluate new multilateral commitments differed – Democratic respondents stressed the importance of international legitimacy, while Republican respondents were likely to favor protecting U.S. sovereignty and freedom of action (Figure 4).

Looking ahead, we see great potential for a better understanding of where our country’s leaders stand in relation to one other and the mass public. As one of us recently blogged on the Duck of Minerva, because our nation’s elites are seldom surveyed about their attitudes on foreign policy, we are often left with rival assertions about what decision-makers think about the international realm, based mostly on the public statements of elected leaders without much information about what they might believe in private, let alone what their staffers think or what other leaders in the private sector, nonprofits, and the military think. Both the academic community and the general public could greatly benefit from revived leaders surveys from the Chicago Council.

Even with our extensive investigation of this topic over the past decade, we are still puzzled to try to understand why the balance of power in the Republican Party has moved away from support for multilateralism in recent decades. Despite finding support for a number of elements of multilateralism when we surveyed elites, we have the sense that politically that the traditional pragmatic internationalists like George H.W. Bush, Brent Scowcroft, and Henry Kissinger may have been increasingly sidelined within the party.

Scowcroft, a former National Security Advisor to two Republican presidents, underscored this dynamic when he recently said in an interview about Chuck Hagel’s nomination for Secretary of Defense:

“We haven’t moved; the Republican party has moved,” Scowcroft told The Cable in an interview. “I have been a lifelong Republican and I hold to what I are my own beliefs, which happen to be core Republican beliefs, but many in the party have taken a different course.”

We think Scowcroft put his finger on something, and we have entertained some arguments to explain what has transpired, but we come back to systematic empirical research. We simply need more data to truly get a handle on both what has transpired and why.

Joshua Busby is a Professor in the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas-Austin. From 2021-2023, he served as a Senior Advisor for Climate at the U.S. Department of Defense. His most recent book is States and Nature: The Effects of Climate Change on Security (Cambridge, 2023). He is also the author of Moral Movements and Foreign Policy (Cambridge, 2010) and the co-author, with Ethan Kapstein, of AIDS Drugs for All: Social Movements and Market Transformations (Cambridge, 2013). His main research interests include transnational advocacy and social movements, international security and climate change, global public health and HIV/ AIDS, energy and environmental policy, and U.S. foreign policy.

I wonder if support for free trade is overstating the GOP’s internationalism.

Josh I’m not sure of the relevance of this to your research but Norrin Ripsman (2011) has a neat little chapter on the practice of bipartisanship in American Cold War security policy. Rather than frame bipartisanship as a shared belief, institutional outcome, or a bargain struck among political elites, Ripsman situates bipartisanship as a ‘practice’ that was sustained by the competency of key policy figures such as Senator Art Vandenberg. When these actors retired or passed away there was no one with the competency to sustain bipartisanship. Have you considered that the necessary competency to sustain bipartisanship might just exist anymore?

Great and helpful comment Eric. It’s certainly hard to capture individual agency in all this. There may be something about how capable the key individuals involved were, but I am struck by Churchill’s observation that the Americans will do everything right after trying everything else first. I do think there is something mythical about the degree of post-war bipartisanship, that it may not have been all that extensive but was certainly enough to give bi-partisan cover for important decisions. One of the ideas we are toying with is the notion of cohort effects based on ideology and hiring practices, that Kissinger and Scowcroft beget a certain number of policy offspring if you will but that their ideological progeny are dying out within the Republican Party at least in terms of structural power within the party if not numbers. That’s a hard thing to show and quite different from the capability of individual leaders.