On the sidelines of the Pacific Islands Forum, Australia and Tuvalu just signed a new, major agreement—the Australia-Tuvalu Falepili Union Treaty.

It binds Australia and Tuvalu much closer together in ways that appear to be win-win. And nobody was coerced into signing it (not directly anyway). But it’s not great, Bob!

The new treaty actually expands the Pacific’s ongoing sphere-of-influence problem—the only problem nobody seems willing to name yet undermines almost every good news story that comes out of the Pacific.

If the region cannot find an alternative to sphere-of-influence arrangements, it will not just lose control of its own fate—any attempt to make the Pacific region more secure will be hamstrung (no matter who’s making the attempt).

Let me explain.

Win-Win for Whom?

The Australia-Tuvalu treaty reifies a lot of important rhetorical and symbolic language about Falepili (neighbourliness, care, mutual respect) and larger Pacific strategy statements (e.g., the Boe Declaration).

That “localization” can be good if it guides politics, bad if it co-opts politics or legitimates power imbalances.

At the core though there are two big things on offer here. One is migration as part of climate adaption; the other is basically the new imperialism.

Climate Migration

As Kate Clayton captures, Australia has opened a visa stream for around 280 Tuvalu citizens to resettle in Australia each year. For a population of 11,200, that comes out to around 40 years before total resettlement/assimilation.

This visa migration offering appears to be Australia’s big answer to Tuvalu facing extinction-level rising seas. This is good, and yet not as it seems.

In classic “let’s not think about root causes of insecurity” fashion, Australia is not arresting fossil fuel reliance or exploration, which contributes more than its share to the global climate crisis that disproportionately impacts nations like Tuvalu. And it is not subsidizing the Pacific’s shift away from fossil fuels (ending fossil fuel reliance in the Pacific was one of the big announcements coming out of the Pacific Islands Forum).

And any number of Australian scholars have been quick to criticize this aspect of the treaty with Tuvalu in so many words—address the symptom or expression of insecurity (with migration allowances) while perpetuating its cause (fossil fuels).

A New Imperialism

Australia could have offered the visa migration scheme to Tuvalu with no strings attached. Instead, just as China has done with its “strategic comprehensive partnerships,” it has embedded a good gesture inside a larger strategic relationship that formalizes authority and an imbalance of power between Australia and Tuvalu.

The treaty makes Tuvalu part of an Australian sphere of influence and the language makes this very explicit:

Tuvalu shall mutually agree with Australia any partnership, arrangement or engagement with any other State or entity on security and defence-related matters. Such matters include but are not limited to defence, policing, border protection, cyber security and critical infrastructure, including ports, telecommunications and energy infrastructure.

The treaty gives Australia veto power over everything to do with “national security” in Tuvalu.

And this is hardly unprecedented in Australian foreign relations. Australia already takes responsibility for the defense of Nauru, and, in conjunction with New Zealand, also provides defense for Kiribati. These two arrangements constitute informal spheres of influence.

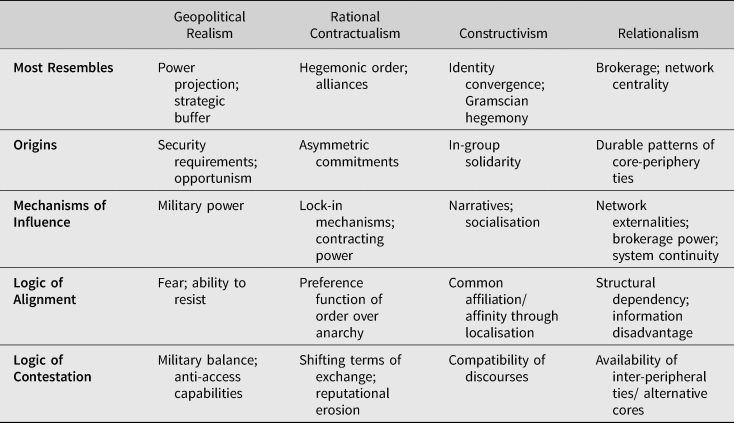

Spheres of influence are practices of control and exclusion—a multidimensional hierarchy that one actor imposes on another. Third parties can respect it or contest it (the multidimensional part), but the exclusionary nature of spheres of influence means that the subordinated party gives up some aspect of controlling its foreign relations. From my research on sphere of influence:

Australia is not alone here. The United States has the largest, most comprehensive, and formalized sphere of influence in the Pacific, and France retains multiple colonies in the Pacific. If you’re thinking, “That sounds very anti-rules-based international order!” well, it depends on whose rules and what rules.

Spheres of influence have often converged with empires and colonialism because sustaining those hierarchical orders entail practices of control and exclusion. But spheres are not inherently bad, illiberal, or even imperial despite tending to be all of the above; it depends.

Tuvalu, for instance, has no military, and since climate change is its highest declared national security priority, any outside support that helps Tuvalu respond to that problem is rational and worth taking seriously. Australia’s climate migration visas do just that. And some spheres are facilitated by mutual affinity or convergent identities, which can imply consent.

In a narrow sense, this is not a bad deal for Tuvalu. It’s actually easy to see why Tuvalu would’ve acceded to this arrangement.

But there’s a way in which this deal provides for Tuvalu’s security at the expense of the Pacific’s security more generally. This one-to-one fashioning of patchwork bilateral “solutions” is part of the larger, more problematic, sphere-of-influence trend plaguing the Pacific.

These arrangements weaken the ability for Pacific nations to act collectively because they give other powers the ability to not just shape and shove but actually direct whether and how security issues are addressed.

There’s Gotta Be a Better Way

It doesn’t have to be this way, but what is to be done depends on how you’re positioned in the world system.

If you are a nation of the Pacific (rather than a Pacific-branded power), the thing you have that outside powers want is your sovereignty. Yes, outside powers want your resources, your territorial space, your UN votes, and your moral authority yoked to their political projects. But the only guaranteed way for them to acquire those things from you is by arranging to circumscribe your control over your decisions.

This is not a hopeless situation.

If you’re Australia, the US, New Zealand, or France, you should, to start with, do no harm. Facilitate meaningful self-determination (contra spheres of influence). Repair past harms. And bet on the centrality of Pacific regionalism as part of any approach to addressing insecurity (this is something that the US talks about but does not do).

If you’re a Pacific nation, your task is far more complicated, because you’re being presented with situations that are full of traps—landmines, poison pills, Sophie’s-choice decisions, and Faustian bargains at every turn. Short-term relief for long-term dependency. Every choice put on you seems, at best, to address symptoms without treating underlying maladies.

The important thing is to understand that the quid pro quo of aid from and intimacy with outside powers deepens Pacific insecurity if it extends spheres of influence.

This is cross-posted at the Un-Diplomatic Newsletter.

0 Comments