I dislike the term “soft power.” We owe the term to the late, great Joseph Nye. He popularized it in his 1990 book, Bound to Lead. Nye’s book was, first and foremost, an intervention in the “declinism” debates of the later 1980s. Japan was at the peak of its influence; some projected that its economy would overtake that of the United States by the early 2000s. Paul Kennedy’s 1987 bestseller, the Rise and Fall of the Great Powers, argued that the United States needed to adjust to its relative decline by reducing its overseas military commitments and reducing its defense spending. Politicians accused Japan and West Germany of exploiting the United States; they called for both countries to increase their defense spending and end “unfair” trade practices.*

Nye argued that international leadership is not only a matter of military and economic might. States have a much easier time leading if people want to follow them. According to Nye, the United States stood for values — democracy, equality, and freedom — with worldwide resonance. Its cultural products — films, music, television, clothing — were widely consumed and emulated. It was home to the most important multinational firms. It occupied the catbird’s seat in most major international organizations. In short, the United States was attractive in ways that no other state could match. As long as it cultivated such “soft power,” it would be able to maintain international leadership even in the face of relative economic decline.

Nye was also writing at a time when realism still exercised outsized influence over debates in International Relations. If the realism of that era stood for anything, it was that only military “power” (read “capabilities”) really, truly matter in international politics. Nye had long argued that realist understandings of power might have been true in the past. But not anymore. In a world marked by increasing interdependence — “complex interdependence” — military power was becoming less useful (less “fungible”).

If military power could be transferred freely into the realms of economics and the environment, the different structures would not matter; and the overall hierarchy determined by military strength would accurately predict out- comes in world politics. But military power is more costly and less transferable today than in earlier times. Thus, the hierarchies that characterize different issues are more diverse. The games of world politics encompass different players at different tables with different piles of chips. They can transfer winnings among tables, but often only at a considerable discount….

Power has always been less fungible than money, but it is even less so today than in earlier periods. In the eighteenth century, a monarch with a full treasury could purchase infantry to conquer new provinces, which, in turn, could enrich the treasury. This was essentially the strategy of Frederick II of Prussia, for example, when in 1740 he seized Austria’s province of Silesia.

Today, however, the direct use of force for economic gain is generally too costly and dangerous for modern great powers. Even short of aggression, the translation of economic into military power resources may be very costly. For instance, there is no economic obstacle to Japan’s developing a major nuclear or conventional force, but the political cost both at home and in the reaction of other countries would be considerable. Militarization might then reduce rather than increase Japan’s ability to achieve its ends.

Over the years, Nye sought to clarify what he meant by “soft power.”

In that climate, and with the invasion of Iraq proving disastrous, I felt I needed to spell out the meaning of soft power in greater detail. Even colleagues were incorrectly describing soft power as “non-traditional forces such as cultural and commercial goods” and dismissing it on the grounds that “it’s, well, soft” (Ferguson, 2009). And a Congresswoman friend told me privately that she agreed 100 per cent with my concept, but that it was impossible to use it to address a political audience who wanted to hear tough talk. In 2004, I went into more detail conceptually in Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. I also said that soft power was only one component of power, and rarely sufficient by itself. The ability to combine hard and soft power into successful strategies where they reinforce each other could be considered “smart power” (a term later used by Hillary Clinton as Secretary of State). I developed the concepts further in my 2011 book on The Future of Power Including in the realm of cyber power (Nye, 2011). I made clear that soft power is not a normative concept, and it is not necessarily better to twist minds than to twist arms. “Bad” people (like Osama bin Laden) can exercise soft power. While I explored various dimensions of the concept most fully in this work, the central definition (the ability to affect others and obtain preferred outcomes by attraction and persuasion rather than coercion or payment) remained constant over time.

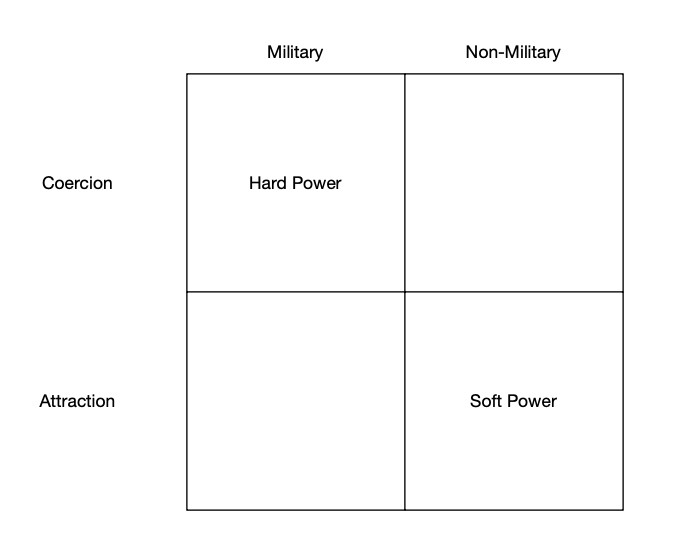

But, as best I can tell, Nye continued to refer to military and economic power as “hard power” and “soft power” as attraction and persuasion via other instruments.

Incorporating soft power into a government strategy is more difficult than may first appear. For one thing, success in terms of outcomes is more in the control of the target than is often the case with hard power. A second problem is that the results often take a long time, and most politicians and publics are impatient to see a prompt return on their investments. Third, the instruments of soft power are not fully under the control of governments. Although governments control policy, culture and values are embedded in civil societies. Soft power may appear less risky than economic or military power, but it is often hard to use, easy to lose, and costly to reestablish.

Soft power depends upon credibility, and when governments are perceived as manipulative and information is seen as propaganda, credibility is destroyed. One critic argues that if governments eschew imposition or manipulation, they are not really exercising soft power, but mere dialogue.” Even though governments face a difficult task in maintaining credibility, this criticism underestimates the importance of pull, rather than push, in soft power interactions. The best propaganda is not propaganda.

So what’s the problem? Nye’s insights are arguably more important than they’ve ever been; “soft power” provides a useful shorthand for explaining how Trump is destroying U.S. global influence.

I worry that the distinction between “hard power” and “soft power” will always devalue non-military (and non-economic) instruments. But I also think, at least in common usage, it collapses two different concerns: the type of capability and the logic of its use. Military capabilities can be used to attract; cultural resources can be used to coerce. But the language of “soft power” and “hard power” — sometimes implicitly, often explicitly — rules out those combinations.

I suspect that most uses of military capabilities are not properly described as coercive — or at least not purely coercive. Washington has employed the U.S. forces for a wide range of purposes, including building social capital with “allies and partners” and as symbols of American prestige and technological prowess.

*Yes, Trump’s attitudes toward U.S. allies are stuck in the 1980s. Why do you ask?

0 Comments