My New Year’s resolution for 2026 is to somehow make peace with reviewing for journals. Something is amiss, at least for me, but perhaps it reveals a larger problem related to journal and book publishing. I kept a running tally of review requests for 2025. Give or take some error, I had 79 review requests, which includes some R&Rs, book proposals, and a several full books. I’m not including tenure letters.

I didn’t say yes to all of them, but I did do more than 30 reviews last year. It’s occupied more of my time and mental bandwidth than I can deal with, and I’ve got to come up with a more productive way to handle them, but I wonder whether there is a broader problem in publishing that is causing a breakdown in the peer review model.

So, in this post, I want to comment on challenges I see emerging in reviewing and assess whether paying reviewers is a potential solution to the problem. In the next post, I’ll deal with my strategies for how to review efficiently and still be fair to the authors.

Why So Many?

On some level, I get why I’m on the receiving end for so many review requests. I’m a reasonably established scholar in the field. I write on eclectic topics that cross-disciplines including energy and environmental policy, international relations, and public health. I also recognize that those who publish a lot should expect to review a lot. For every submission, imagine there are 3 people who have reviewed for you. So, I’ve heard it said, you should try to do 3 reviews for every manuscript you submit. If you submit 5 manuscripts a year, that’s 15 reviews you should be doing.

Still, it’s getting to the point that it’s absolutely ridiculous the number of requests I get and the amount of time potentially involved in largely unpaid labor that is a service to the field but largely unrewarded and unrecognized by the university.

Is the Model Broken?

Since the COVID pandemic, editors report that it has become increasingly difficult to find reviewers for manuscripts. It often takes more invitations to get acceptances, and there may be increasing challenges of getting timely reviews. According to one study, pieces where it was more difficult to find reviews are less likely to get published.

A story in Science noted that even before COVID that editors were having to ask more and more people to carry out reviews. This is not field specific so I don’t know the numbers for IR but, I imagine that this is even worse now.

In 2013, journal editors had to invite an average of 1.9 reviewers to get one completed review; by 2017, the number had risen to 2.4, according to a report by Publons, a company that tracks peer reviewers’ work.

There are also may be both a proliferation of submissions and journals as a result of increasing expectations of publications, that starts earlier among graduate students and where metrification by departments leads to pressures to publish quantity as much if not more than quality publications. With more submissions from scholars from around the world, there just may be a lot of material to review. I also worry that with AI we may see even more submissions and a proliferation of fraud.

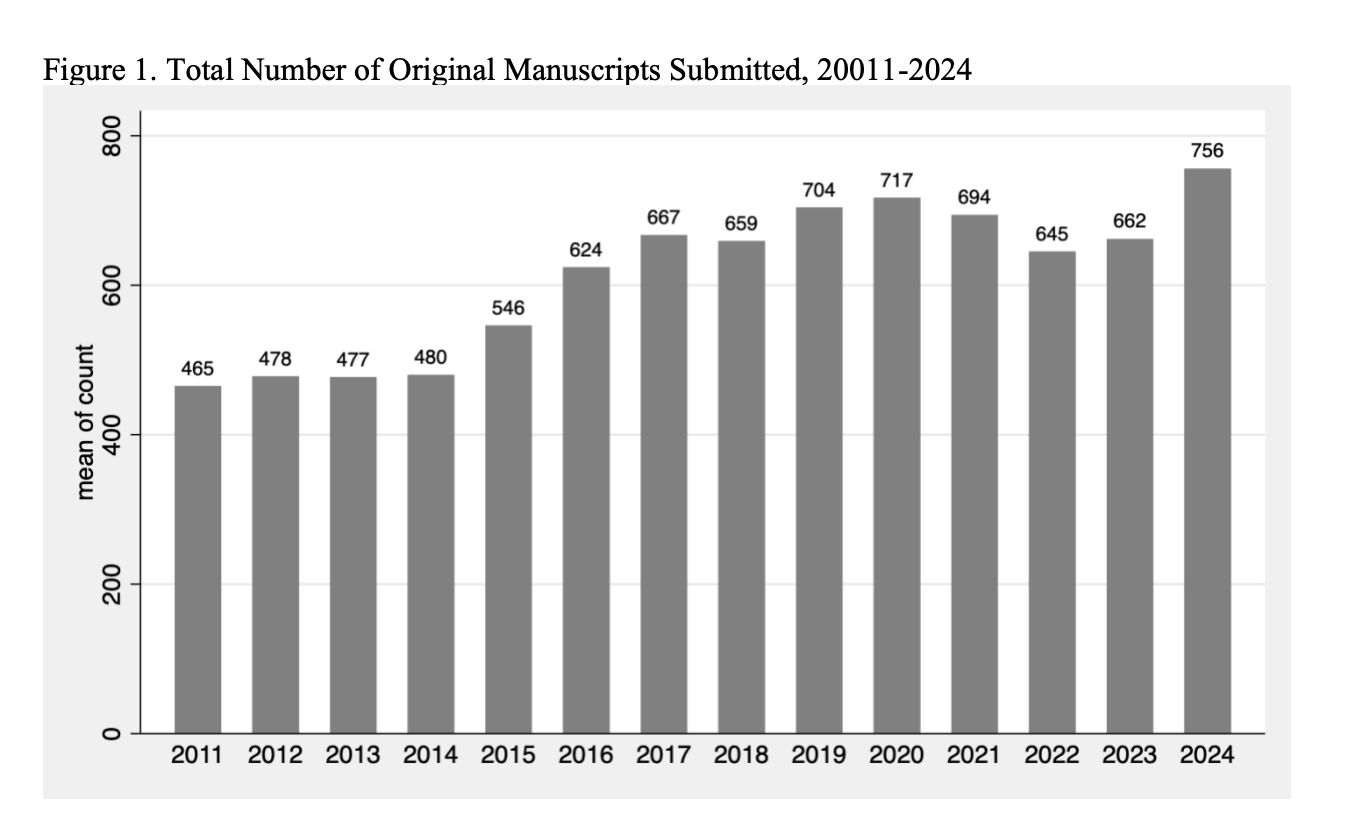

As I’m sure my Duck colleague Dan Nexon knows all too well, all of these pressures show up in an increasing volume of submissions to journals. Take International Studies Quarterly which Dan edited for 5 years. Here is the increasing volume of submissions from 2011 to 2024, with a bit of a dip post-COVID. ISQ during academic year 2023-2024 had a higher desk reject (nearly 50%) than previous years so that meant fewer pieces were sent out for reviews. Among those sent out for review, about 40% of review requests were declined. The annual note didn’t speak to the trend here.

The increasing challenges associated with peer review is not a new problem in political science. A piece in PS by Richard Niemi in 2006 lamented that the demands on professional time for reviewing and the challenges of findings reviewers. He identified diverse reasons for why the problem was getting worse : (1) the proliferation of journals, (2) expanded number of issues per journal, (3) more non-US based journals, (4) more international submissions, (5) more use of 3 rather than 2 reviewers, (6) increasing niche specialization of authors making it more difficult to find compatible reviewers, (7) more methodological sophistication that made finding reviewers with particular skillsets challenging, (8) fewer articles being accepted outright so more R&Rs and (9) expectations for graduate students to publish.

What Should be Done?

Niemi identified a range of measures to address the problem, some of which involved more desk rejects and higher barriers to entry to publish papers, including payments to journals. These were measures mostly to restrict the supply of journal articles. In terms of incentivizing more reviewers, one option he identified was payment for reviewers and other ways to increase the recognition for those who do a good job reviewing, saying yes, delivering reviews on time, and writing substantively helpful comments. Some of these recommendations had to do with reestablishing norms of civility and professionalism, but few of these dealt with challenges based on the volume of submissions and concentration of requests on particular people.

This may have happened already but journal editors in international relations and related fields might want to produce a cross-journal report documenting whether the trends are getting worse in terms of numbers of submissions and difficulty of finding reviews.

I also wonder whether efforts to allow people to be recognized for doing good work for reviews through Publons or Web of Science allows editors to identify people that they can then ask for reviews. If that is happening, there is a perverse incentive not to be recognized for reviews, because recognition as a reviewer makes you a target to get more review requests.

Should Reviewers be Paid?

There is an argument to pay reviewers to compensate them partially for their time. That would perhaps change the incentive structure a bit so people would be willing to say yes and do reviews in a timely manner. If you are getting paid, you might put a little more thought in to what you say.

While book presses pay modestly for reviews, journals don’t and I wonder if that should or can change. There was a movement a few years back in the natural sciences to seek some $450 for reviews, which seemed to me highly implausible, but a lower number might work and not break the bank of journals.

I don’t have a handle on whether the publisher business is a lucrative one. You hear periodically about publishers being successful on the backs of the pay-to-publish models. This story on Elsevier’s parent company suggested the company had an adjusted operating profit of more than 1.17 billion pounds or $1.5+bn in 2024, much of it driven by the open access model.

Paying for reviews could have some perverse incentives of its own. There could also be quality issues as people might carry out inferior reviews just to get paid, which might require more extensive tiering of payments for reviews based on quality but not simply on word length.

In the Science article I mentioned, there were some good exchanges on the specific $450 per review model which again seemed high in my mind. Here is an anti view:

T.V.: An average of 2.2 reviews per article is very typical for journals. And [assuming each reviewer is paid $450,] each reviewed article therefore costs $990. Of course, an APC or article-processing charge [required by some journals to make articles free to read on publication] is only paid by the articles that get accepted for publication, and the cost of reviewing the rejected ones is loaded into the APC. For a journal with a 25% acceptance rate, they have to review four articles in order to find the one that they accept. Multiplying by four gives us $3960 [to cover the costs of review for each accepted paper].

That particular debate seemed skewed against payments for publishing, but other experiences have been been more positive. Some experiments in the natural sciences found that paying reviewers about $250 per review sped up review times and acceptance rates compared to unpaid reviews. In one experiment, they found, “The average turnaround time for paid reports was 4.6 business days, compared with 38 days for reports not involved in the payment trial. Editors found no difference between the quality of paid and unpaid reports.”

Even if reviews were unpaid, another option would be to create credits with publishers for open access publishing fees from the reviews that were conducted, though that would require a system that allows you to convert reviews into a currency that could be transferrable to another journal, as you may review for one journal and publish at a different one. Getting paid actual money might be simpler.

The challenges of moving to this system would be the administrative burden of managing a payment system, but how much more burdensome is that to the current system which already requires reviewers to have pretty extensive information about them collected already?

I don’t know if any political science journals have experimented with payments for reviews but it seems like the current system isn’t working all that well, but it may be part of a broader seismic shift in publishing that we’re experiencing or about to with pay to publish models and AI.

All I know is that the current system isn’t working well for me, and in my next post, I’ll talk about strategies that I’ve taken to try streamline how I do reviews and still be fair to the authors.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks