I am happy to guest post my friend Dave Kang of the University of Southern California. I think Dave’s work on east Asia and IR theory is excellent; I would start with this or this if you’re interested. REK

|

| Figure 1. Korean Worker’s Party symbol |

It is easy to caricature North Korea as a “bizarre” “land of no smiles” full of brainwashed robots. In the past few years, North Korea has become somewhat prominent in popular culture either as a salacious joke or a freak show of a country. (And yes, I refuse to give you too many links to articles I think are misinformed caricatures). The trope of North Korea as a nation of automatons, grimly marching through each day is very powerful.

It is absolutely true that the regime itself is horrific and reprehensible, and engages in systematic human rights abuses. Indeed, the people of North Korea are the most direct victims of the ruling regime. I am totally for regime change, or a regime that modifies its ways and introduces economic and social reforms that improve the lives of its people. However, wishful thinking has gotten us nowhere, and rather than simply sit back and laugh at North Korea or call it names, perhaps we might explore why the regime has survived as long as it has.

In addition to extensive repression and selective bribery, what is widely overlooked is that the North Korean dictatorship is built on deeply traditional Korean cultural and Confucian roots. In fact, the best way to understand both the regime and its people is to remember that North Koreans are Koreans more than anything else. Far more insightful than any other description such as “communist monarchy,” North Korea is identifiably Korean, and there is a coherent internal logic in much of its way of life. As a result, the regime is more stable and enduring than commonly thought. (The arguments I make here have been made much more cogently by Bruce Cumings and Suk-Young Kim, among others).

Take a look at picture at the top of this page, which is a photo of the official emblem of the Korean Worker’s Party. Although the hammer and sickle are easily recognizable as signs of all Communist Parties from the Soviets to the Chinese Communist Party and others (Figure 2),

|

| Figure 2. Flag of the Chinese Communist Party |

North Korea is unique in that there are actually three symbols. What is that middle symbol in Figure 1?

1. Candle?

No. Wrong. C-

2. Paintbrush?

Warmer. What kind of paintbrush?

3. A calligraphy brush they used in olden times to write Chinese characters?

Yes!

It is a Confucian scholar’s brush – perhaps the most direct and vivid symbol of traditional learning, culture, and scholar-elite rule in Korea since the 9th century Silla dynasty first introduced an examination system for selecting government officials.

This is pretty remarkable. The Communist Party everywhere has stood for an utter rejection of the past and tradition as feudal and oppressive, and the basic message from Stalin to Mao has been to destroy the past and totally rebuild society. Yet the North Korean regime, rather than attempting to erase the past, has grafted itself onto traditional Korean traits, and reached back to some of the most traditional iconography possible: a hierarchic and elitist symbol of education, with all the other Confucian connotations that go with it: a ruler who embodies both the country and the “mandate of heaven,” an emphasis on centralized political control, and a clear set of hierarchical relationships that create harmony.

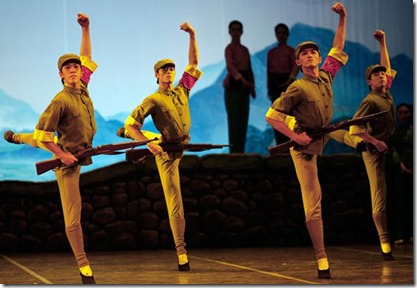

What about the role of women? Figure 3 is prominently displayed in Pyongyang, and depicts a generic and heroic “Mother,” fighting against the Japanese.

|

| Figure 3: “Mother in a Sea of Blood” |

What is interesting about that painting? As with the KWP symbol, it might strike the viewer as somewhat odd that she is wearing traditional Korean women’s dress (“hanbok,”or “choseonot” as they call it in North Korea). Compare this with the standard depictions of revolutionary Communist women from China or the Soviet Union – they are all in drab “Mao jackets” that reject and depart from any traditional and feudalistic tendencies (Figure 4).

|

| Figure 4: Chinese Revolutionary Women |

But in North Korea women have been presented with an image that emphasizes their Koreanness – a traditional dress that is far more common in Pyongyang and North Korea than in South Korea. The regime explicitly is telling North Korean women that they are a link to a way of life that is Korean, and the way they dress is the most obvious manifestation of that link.

What about the “cult of personality” and the rise of the grandson? Surely that’s bizarre, right? Not really, in a traditional Korean context. The Confucian emphasis on family places the father as the head of the family. Kim Il-Sung simply placed himself as father of the country, and grafted an authoritarian state onto the existing social and cultural roots. Leadership by a powerful family makes sense in a Korean context. Korea is a clannish country, and the family is the basic building block of social, political, and economic life.

The best way to understand the role of families is by comparison with contemporary South Korea. The foundation of Korean life in both North and South is the clan. For example, most major business conglomerates are family-run, and often the grandson of the founder is now in charge. This is the case even of the biggest companies in Korea. In addition, it may appear to outsiders that Korea is a country with only three last names (Kim, Park, and Lee, hahaha). But all those Kims are actually divided up into dozens of different clans, each connected to a hometown, each with extensive family lineage records, and each vividly distinctive to other Koreans. Thus, there is Kimhae Kim, Seoul Kim, Kyongju Kim, etc. So powerful was the clannish nature of Korea that until 1998, members of the same clan could not legally marry, even if they were separated by tens of generations. Similarly, Kathy Moon has recently argued that the blather over Kim Jong-un’s marriage is mostly misguided: “For Koreans on both sides of the 38th parallel…Unless one is married (and with children), one is not fully an adult. In both Koreas and in dynastic cultures, those pieces are supposed to come in the same box, to be pieced together into a coherent puzzle.” Thus, within a Korean cultural context, multigenerational leadership in North Korea and family as the building block of society is common sense.

Why does this matter? Because the story the North Korean regime tells itself and its people is aimed at domestic audiences, not at international audiences. They are telling a story that — however warped and corrupted — resonates deeply and instinctively with Koreans: North Korean are the true Koreans, and are the only ones remaining true to the essence of being Korean. South Koreans have been corrupted and forgotten who they are. The Kim family is leading the fight against external oppressors such as Japan and America. If the people must endure some hardship in order to maintain a Korean way of life, that’s a small price to pay.

This is one reason I tend to think an Arab Spring or uprising is not likely. Questions of imminent demise overlook the fact that North Korean dictatorship has grafted itself onto deeply traditional Korean culture roots. As a result, the regime is much more stable than some may think. For some people of North Korea, conditions may become so horrific that they choose to try and leave. But far more remain, and they remain not because they are brainwashed and not only because of repression. Many stay because North Korea is their home, where they grew up, where their family and friends live, and it is what makes sense to them.

Associate Professor of International Relations in the Department of Political Science and Diplomacy, Pusan National University, Korea

Home Website: https://AsianSecurityBlog.wordpress.com/

Twitter: @Robert_E_Kelly

David Lai made a similar argument https://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/index.cfm/articles//Busting-the-Myths-About-the-North-Korea-Problem/2012/02/23