The controversy surrounding the coalition airstrike in Kunduz continues to rumble on this week after military investigators drove an armoured personnel carrier into a hospital’s front gate. A spokesperson for the Pentagon was quick to apologise for any damage caused, telling reporters (without a hint of irony) that the team were simply trying to gain access to the facility so that they could assess the structural integrity of the buildings hit earlier in the month. This latest incident will do little to ease tensions between the United States and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which operates the hospital. Three separate investigations into the original attack are now underway but there is still a great deal of uncertainty about why the hospital was targeted. What we do know is that at least 22 people were killed when the AC-130 gunship opened fire on the building, including 12 medical staff and 10 patients.

The debate so far has largely focused on whether or not the attack was lawful, but what caught my attention was the response of the military officials and, in particular, their offer of compensation. After initially blaming ground troops for the mistake and then the Afghan Army, the Pentagon eventually admitted the decision was made further up the chain of command and President Obama has now offered a full-blown apology. What is more, it has since been confirmed that the United States will compensate the victims and help rebuild the hospital. As the Pentagon press secretary Peter Cook made clear, ‘the Department of Defense believes it is important to address the consequences of the tragic incident’. But the use of financial compensation to rectify these wrongs raises a number of important ethical questions: Do these payments actually make the perpetrator any more accountable for the harm they have caused? Is there a risk that they may end up normalising the horrors of war? And do they reflect a genuine concern for the pain and suffering experienced by those living on the frontline of today’s conflicts?

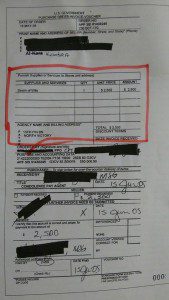

The payment of compensation for “collateral damage” is not something that is unique to the attack on Kunduz but a fairly routine feature of counterinsurgency operations in both Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2005, for example, more than $19 million was paid out in compensation in Iraq alone, whilst records obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union suggest that millions more have been spent in the battle for hearts and minds. The problem is that this meticulous accountancy does not necessarily lead to greater levels of accountability, as Emily Gilbert makes clear in a recent (and rather brilliant) article for Security Dialogue (see also). What worries Gilbert is that these condolence payments become an incredibly insensitive, technical and bureaucratic way of dealing with the death and destruction inflicted on the battlefield, amplifying a sense of impunity within the military. In order to illustrate her concerns, she points to an “invoice” gleaned from the ACLU archive, which was given to a bereaved man in Iraq. In the column labelled “supplies and services”, we find a single entry for the “death of wife” and a “unit price” of $2,500 (see below).

The payment of compensation for “collateral damage” is not something that is unique to the attack on Kunduz but a fairly routine feature of counterinsurgency operations in both Afghanistan and Iraq. In 2005, for example, more than $19 million was paid out in compensation in Iraq alone, whilst records obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union suggest that millions more have been spent in the battle for hearts and minds. The problem is that this meticulous accountancy does not necessarily lead to greater levels of accountability, as Emily Gilbert makes clear in a recent (and rather brilliant) article for Security Dialogue (see also). What worries Gilbert is that these condolence payments become an incredibly insensitive, technical and bureaucratic way of dealing with the death and destruction inflicted on the battlefield, amplifying a sense of impunity within the military. In order to illustrate her concerns, she points to an “invoice” gleaned from the ACLU archive, which was given to a bereaved man in Iraq. In the column labelled “supplies and services”, we find a single entry for the “death of wife” and a “unit price” of $2,500 (see below).

The money allocated for different types of injury is fairly arbitrary, but there is some leeway to accommodate local customs and expectations. According to Gilbert, the loss of a limb generally attracts $600-$1,500, property damage tends to have a maximum limit of $500 and a car can be worth as much as $2,500, which is the same value attached to a person’s death. Other countries have their own pricing structure and there are, of course, interesting comparisons to be made with past conflicts. In her new book The Politics of Wounds: Military Patients and Medical Power in the First World War, Ana Carden-Coyne draws attention to the extraordinary pension system that was created in the United Kingdom in 1917. An additional grant was paid to soldiers who were injured on the battlefield. A soldier who lost two or more limbs would get the full grant, whereas a soldier whose leg was amputated at the hip would only receive 80 per cent. Amputations above the knee were worth 60 per cent but below the knee were only worth 50 per cent. Of course, the amount of money received was dependent upon the soldier’s race, rank and class. The body of an officer was worth more than the body of lowly squaddie, whilst Commonwealth soldiers were considered to be ‘physically and morally weaker than white soldiers’. As always, certain bodies are seen to be much more valuable – and more valued – than others.

Of course, it would be a mistake to dismiss these payments out of hand because they undoubtedly provide some degree of relief for the families of the dead and injured. Human rights groups have argued that this money can help to keep food on the table following the death of a family breadwinner and alleviate the financial hardships caused by the loss of crops, damage to the home or the destruction of a local business (see also). But the low value attached to the lives of those lost and the perceived lack of accountability has inflamed tensions between military personnel and local civilians. At the same time, the language used across a range of military texts indicates that these payments are not primarily concerned with recognising the loss of countless others but with controlling and managing unrest. A number of counterinsurgency documents (here, here and here) refer to money as a ‘weapon’ or ‘weapons system’, suggesting that the swift payment of compensation is crucial to securing the hearts and minds of local people. Gen. David Petraeus even went as far as suggesting that ‘money is my most important ammunition in this war’.

Even the language used to describe these payments suggests that they are not really a mechanism designed to promote accountability. The US Army’s Civilian Casualty Mitigation protocol, for example, explicitly states that this money is an ‘ex gratia payment (compensation without obligation or liability)’ and warns that soldiers should be alert to ‘fraudulent claims’. Field Manual 3-24 also makes clear that these payments are not meant to indicate legal or moral responsibility, but should be seen as an ‘expression of sympathy or condolence’. The danger here is that this commodification of civilian harm encourages the very thing it is supposed to restrain, cultivating a sense of impunity amongst the troops by providing a technical fix to an ethical problem. The offer of compensation to the MSF following the attack on Kunduz is clearly an important first step, but it should not distract us from more fundamental questions about the tactics used to legitimise contemporary practices of war.

Tom Gregory is a lecturer at in the department of Politics & International Relations at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. His research focuses on contemporary conflict, critical security studies and the ethics of war.

0 Comments